Jan 30, 2020

Happy new year!

I spent November preparing for Christmas markets, so pricing has been on my mind.

More than usual, that is, because since I'm a self-employed leftist it's not like it's ever far.

Let's skip the niceties: most artists and crafters out there are underpricing brutally,

it's making my life harder and the field worse, and I'm annoyed.

So here's a three-part primer:

why underpricing hurts everyone,

how you can get a semi-decent estimate of what you should charge,

and how this ties into armchair economics and political positions.

ONWARDS.

The race to the bottom

Factory-made goods are so, so cheap.

Mechanization sped processes up by several orders of magnitude,

and reduced labor costs immensely.

Manufacturing was also moved overseas,

quite often to take advantage of lower wages in some countries.

This is very obvious with textiles:

the linen cupboard used to be a literal treasure in every household,

but these days textiles are very affordable,

quickly bought and discarded.

This is not a good or a bad thing per se.

Affordable textiles are great,

textile waste is bad.

My point here is that it pushes perceived value down.

It can be tempting, as a small-scale artisan, to set your prices to the same level.

Pricing is difficult, and working from what we know is easy.

It also makes it seemingly simple to sell handmade things,

get money back to buy more supplies and clear the shelves for new projects.

So you sell a handmade mug for 10 dollars,

a hand-knit scarf for 300 swedish crowns,

a handwoven blanket for under 100 euros.

And you forget to account for the time you spent working on it.

This is a fallacy. You can't compete with factory-made goods. It's impossible.

You can't compete with a machine optimized for speed while doing everything by hand.

You might get some sales,

but by setting prices so low,

without accounting for your work time,

you're hurting anyone who is trying to make a living off small-scale handmade goods.

That might include yourself, if you ever decide to try and turn your hobby into an actual business!

By pricing your products like they're factory-made,

you're positioning yourself in the same market as large companies.

Small-scale handmade goods are often high quality and unique:

by making them available at prices equal to uniform factory goods you're erasing that difference.

How does this hurt us?

When other handmade products are available at low prices,

we have to spend extra time justifying our prices,

explaining the difference.

When compared with factory-made goods, we could just say "this is handmade".

Instead, we have to explain our entire pricing strategy and that our labor has value.

The true culprits are unquestionably mass consumption and capitalim:

but by devalueing your labor, you also create unfair, unsustainable competition.

But how do you even put a price on your labor?

Don't worry, I'm not here just to yell at you.

The next part explains how I set my prices,

and why they're so high.

Pricing basics

I'll present the method I use to calculate my own prices.

That means context is important and needs to be adjusted for your own situation:

there are a whole bunch of spreadsheets online for that.

You can use any tool designed for freelancers,

because as an independent artisan that is what you are!

You just sell finished products rather than a service,

and your hourly rate gets turned into a product price rather than a client invoice.

My own context is as follows:

- Living and working in Sweden, where I pay my taxes;

- Salaried through my own aktiebolag (LLC equivalent);

- Ballparking my take-home pay to 50% of what I pay myself to account for taxes;

- Registered for VAT, which is 25% on most of what I sell, though that is ignored in the math below;

- Numbers are written European-style: 20.000 is twenty thousands, not twenty;

- You can roughly translate 10 SEK to 1 USD or 1 EUR. That won't be accurate but it's close enough.

The first step is to figure out how much you need per month.

For me, that's 20.000 SEK after taxes.

And you might argue that this is a high number:

but I live in an expensive town,

and want to be comfortable and pay back my darn mortgage,

not scrape by and live paycheck to paycheck.

This is an acceptable attitude to have:

you're not "entitled" for refusing to struggle.

Add taxes, and I need 40.000 SEK coming in each month.

This is not quite accurate, since taxes work out a bit lower when you're salaried through a company.

But it's a good ballpark for the self-employed status (enskild firma),

and the extra wiggle room covers some fixed overhead.

A month is 4 weeks. So I need 10.000 SEK a week.

A fulltime week is 5 workdays. So I need 2000 SEK a day.

A fulltime workday is 8 hours. So I need 250 SEK per hour.

That's my rock bottom rate.

Anything below that and I'm actively underpaying myself.

Ideally, I want to charge way more than that so I can work less and preserve my health:

that is very easy for programming work, where rates are high,

and very difficult for weaving.

Then, I track work time on every project.

How many hours spent designing, counting, warping, beaming, threading, sleying, tying on, tying up, weaving, finishing, sewing?

I use the same rule as I do with freelance work: "Would I do this if I wasn't working on this project?".

If no, then it's billable time.

Multiply hours spent by hourly rate, and that's the labor costs for a project.

To that labor cost, I add the cost of materials.

I divide the total by the number of pieces in the project,

adjusting for differences in size or complexity if relevant,

and I get my pre-VAT price.

If I charge anything below that price I'm losing money.

Now that I have significant experience,

I can generally run rough estimations of how long a project will take.

This allows me to calculate a preliminary price

and figure out if the project is even likely to sell.

See the Twitter thread when I ran through one such estimate.

The fun part about those high prices?

They are still not high enough.

A healthy business has margin on its products,

so it can invest and grow.

Retailers and galleries often take at the very least a 50% commission,

meaning I'd need to double my prices,

because you should not undercut your own gallery.

What this math gives me is the absolute minimal price,

the one I can't go below.

I can charge what I charge because I'm only selling direct to customers for now.

In the future, I'll either have to get a lot faster - and I'm not that slow to begin with -

or raise my prices significantly.

You'll notice that market prices for industrial goods are at no point something I look at here.

It's not the same market.

Oh, hi Marx!

As mentioned in the intro, I consider myself a leftist.

My pricing strategy ties into that.

With apologies to any actual economist reading this,

I'll now explain why I consider pricing my work fairly to be political.

We're commonly taught about supply and demand and basic market economics:

people want or don't want your stuff at a certain price point,

and you adjust accordingly to find the sweet spot between high sales and high price.

The result is supposedly the Invisible Hand Of The Market magically setting fair prices for everything.

But this is only one way to look at pricing, not a natural law.

Some proponents of this way to look at things push it a step further,

and argue that value is assigned by the market.

A product has no value unless someone is ready to buy it.

Another way to look at this is the labor theory of value.

Now, as mentioned, I'm not an economist so I'm going to oversimplify and probably get details wrong.

But the rough idea is that value comes from the labor embedded in a product.

Be that extraction from nature, transformation, transport:

the time spent by workers is what gives value to a product.

Whether or not someone wants to buy it, the product has value.

See how different those outlooks are?

One trusts markets to know best and wants to leave them to figure it out.

The other one puts value on labor and people.

One is associated with conservatism and the right-wing,

though it has contaminated a large part of the modern left.

The other one is typically associated with Marx and radical leftism.

There are endless arguments among economists about what the "correct" theory is.

To be honest, I don't really care.

Because cheap textiles are (inaccurately) associated with ignored feminine labor,

oppression of workers in non-Western countries,

and deconsideration of crafts skills,

valuing my own labor and pricing according to the time I spent is political.

It means educating customers about the process,

about the true cost of the goods we use.

And while that's time away from making, it's obviously valuable,

especially as we try to build a society that is more in harmony with the world around us.

It is absolutely awful that the result of paying myself a living wage is prices that are not affordable to most people.

For my own practice, it means trying to stay within "comfy middle class" products

rather than focusing on full-on luxury price ranges.

That means series rather than unique objects,

it means selecting techniques that are not too time-consuming.

And it means figuring out new and exciting ways to chop fabric up in small, affordable pieces,

as I'm doing with the dye house / coasters Kickstarter.

I don't yet know where I'll end up.

It probably won't be full-time weaving.

It definitely won't be exclusively taking commissions for rich people,

if only because a twinge too many of them want me and my friends dead by way of inhuman economical policies.

If, like me, you're frustrated by the lack of middle road between underpricing and luxury,

stay tuned.

I'm not giving up just yet.

End notes

A friend helpfully pointed out that William Morris had thoughts and strategies along those lines.

I wasn't familiar with that part of his work, and will research it further.

I also oppose factory-made goods to handmade goods for the sake of keeping the article a reasonable length,

but that dichotomy is an oversimplication.

Ezra Shales' excellent book "The shape of craft" explores those nuances, and is well worth a read.

Dec 12, 2019

It's 2019.

We have machines to do everything.

Robots are taking our jobs, software is eating the world.

The only reason humans are still involved is that some machines are too complicated to make, for now.

So why weave by hand in 2019?

Why do things the hard, slow, expensive way?

This will be a somewhat rambly exploration of common arguments given in favor of making things by hand,

specifically textiles,

and my own approach to that question.

It will oversimplify some things and leave aside some complex matters that deserve their own piece.

Slow fashion

The evils of fast fashion are a common topic in textile,

especially in eco-conscious Sweden.

Sewing your own clothes, weaving your own fabric can then be a militant act.

Handmade things have better quality, or so the idea goes,

and they won't have weird chemicals in them,

or exploited labor in the production chain.

Natural dyeing is so much better for the planet.

Obviously this is an oversimplification:

the waste of products and energy is much larger with handmade goods.

With industrial scale comes efficiency - if only to increase profit.

A lot of the discussion is scaremongering about synthetics and chemicals.

Labor costs are much greater, but hobby makers don't count labor at all,

and many professionals are underpricing theirs brutally.

What slow fashion does have going for it is an encouragement to consume less.

Do we really need that many clothes, new things every season?

But fewer textiles doesn't have to mean handmade textiles:

I've personally been wearing fast fashion T-shirts threadbare over years,

and am starting to consider replacing my 25-year-old bath towel.

Slow fashion and ecological concerns, while important, are not what push me to weave by hand.

If only because as written above, many of the arguments strike me as scientifically questionable.

Tradition

Weaving is ancient.

It goes back thousands of years,

and even very elaborate techniques and tools were invented several centuries ago.

The Jacquard loom wasn't the first computer:

it just put into punch cards what the Chinese did with string way back in BCE.

Sweden was rural for a very long time,

organized in groups of farms that made nearly everything they used.

Go two generations back, and every family had at least one loom.

For many Swedish handweavers, the practice is about keeping traditions alive,

rediscovering and preserving patterns tied to a specific place,

and some fluffy idea of culture.

I'm from France.

My home country was industrialized early,

and making things yourself soon became about hobbies or excellence.

When we speak of preserving crafts traditions, it's not on the same scale:

it'll be old workshops, semi-industrial machines, manufactures.

When it's about individual skills, it will be about haute couture or other luxury goods.

For weaving, some examples are the Manufacture des Gobelins continuing to develop tapestry weaving,

and a couple companies in Lyon preserving silk weaving on ancient looms.

The factories in Northern France have mostly been turned into fancy apartments,

and La Manufacture des Flandres is now a museum,

showing the stages from the medieval handloom to the modern weaving machine.

While I like to learn and help preserve knowledge, it's not what drives me.

I can't in good conscience claim to preserve a tradition I was never a part of,

nor am I interested in repeating old patterns.

Self-care

Making things by hand is good for the modern worker, writes yet another large newspaper.

Could crafting solve the mental health crisis?

Just go pet clay for a couple hours, it'll prevent burnout.

You don't need union fights when you can go to an "office detox" at the end of a workday.

I'm the first one to make a case for every person having several energy buckets:

different tasks drain and fill different buckets,

and variation is good for most people.

Studies show a genuine positive impact,

but I still don't think crafts will save anyone from late capitalism and bad work conditions.

I've burned out. I'm burnt out.

I'm not sure it'll ever heal fully.

Leaning more into crafts wasn't so much self-care as a lack of other choices,

because I could not go on with programming and gamedev alone:

I needed to find something I had fun with again.

I then proceeded to almost burn out on my hobbies,

and again while studying weaving at HV.

So this is definitely not it.

Process nerdery

Weaving is complex,

or more accurately, it can be complex.

You can do a lot with plain weave,

like the rich illustrations of tapestries.

You can play with color and texture while sticking to very simple structures,

like in rag rugs.

But you can also go up to dozens of shafts,

draft mathematical theorems about woven structures,

adjust every stitch in a Jacquard-woven damask so it'll be perfect.

Like a good programmer,

I love systems,

complexity blooming from first principles,

emergent patterns and structures.

My interest in a Jacquard loom isn't so much to be able to weave illustrative pictures,

but that setting up more than 20 shafts would get really annoying.

As my math teacher said:

"To be good at math, you have to be lazy. But not too much".

I don't want the easy way out, but I do want to be smart about doing things efficiently.

Whether it's making complex shapes appear from a simple 8-shaft twill,

or overcomplexifying a traditional lace weave into a 10-shaft block extravaganza,

I like to take traditional structures and make them richer, more complex, more emergent.

It scratches the same itch as putting together a good API,

sliding the last component of a system in place,

and watching the computer do exactly what you wanted it to do.

Remove the locking pin, pass the first few wefts,

and see the cloth take shape, exactly as designed.

It's about the process,

and about a love of making STUFF.

Sometimes that stuff is software,

sometimes it's fifteen meters of delightful linen.

The major difference is that with weaving,

I work from materials and process,

more than the expected or desired final result.

What do I want to work with?

What's a good excuse to work with that?

But it's not about aimless play either.

Once the materials and the technique are chosen,

I make a plan,

I validate the choices by drafting or testing or sampling,

and I follow the plan,

adjusting only as required.

I'm a perfectionist:

not by always finding flaws in what I made,

but in always aiming to meet my own high standards,

and rising them every time.

Things that don't exist

Handweaving is still used in the textile industry.

It's impossible to beat when it comes to iterating quickly on small pieces.

Designers for major textile companies will draft their designs in a handloom,

testing patterns and materials.

You can't just go and setup hundreds of meters of something unproven.

It means small-batch making is at the heart of handweaving.

While that's what makes it unaffordable for most people,

it's also what allows me to make things that would not exist otherwise.

If I want to make a dozen towels with pride flags on them?

I can just set it up and go.

There's appeal in that freedom,

and in the political opportunities it creates.

The obvious sidenote

This entire ramble is written from a Western, industrialized perspective.

Production handweaving for daily use is plenty alive in many countries,

and not as a hobby as it generally is in Sweden.

I suggest looking at Textile Trails,

keeping an eye on Abby Franquemont's projects,

or following Marcia Harvey Isaksson's continuation of "Weavers in the West" over on Instagram.

Sep 30, 2019

Getting good selvedges in handweaving is notoriously tricky.

It's not an issue when making fabric that will be sewn into clothes:

but when creating scarves, blankets, bedsheets or other convenient rectangular items,

clean and sturdy selvedges are marks of a competent weaver.

How the shuttle is passed and at what angle makes a major difference,

but that's not the topic today.

We're instead going to look at how the weave structure itself sometimes makes the selvedges messy,

and how to adress that problem.

It's all about the last threads on the side of the warp.

In plain weave, every thread will change shed with every pick:

this mean that the weft will always wrap around the very last thread.

That creates a stable selvedge, where the only - non-trivial! - problems to solve

are warp density in the reed and weft tension.

But as soon as we move to twills, problems appear.

New weavers often wonder why their twill selvedges look good on one side, but a mess on the other:

it's due to the last thread(s) staying in the same shed, preventing the weft from wrapping around it.

In certain drafts, notably in a simple 2-2 balanced twill,

this will result in warp ends never getting bound at all on one side.

The schematic below show how things look with the weft loose:

examine the path of the weft, and see how it never never loops around the last warp end on the left side.

Note that for extra confusion, which side is messy will vary depending on the treadling in relation to the shuttle direction.

For example, if the last thread stays in the same shed between treadle 1 and 2,

but switches shed between treadle 2 and 3,

the selvedge will be fine if the shuttle is on that side between treadles 2 and 3,

but remain unbound if the shuttle is on that side between treadles 1 and 2.

This is what makes balanced even twills especially problematic:

the shuttle direction will always be in sync with the treadling,

and the unbound side will always be the same.

See the schematics below for how things look after the weft is pulled in,

and which warp end is up loose depending on the direction of the first pick.

2-2 balanced twill is an easy and especially pathological example,

but other structures can have similar problems.

Satins that use many shafts will rarely bind on the selvedge.

Complex twills may end up with random-looking warp floats on the sides.

Those floats can make the cloth weaker, and look messy.

So how do we fix them?

One solution can be to leave the last thread on each side unheddled,

and manually ensure that the shuttle goes around them.

Staying consistent is key:

the weaver needs to remember that, for example, the shuttle goes over the first thread when entering,

and under the last thread when exiting.

This will artificially bind that thread in plain weave, creating a cleaner edge.

But since different structures have different take-up,

that last warp thread will eventually have different tension.

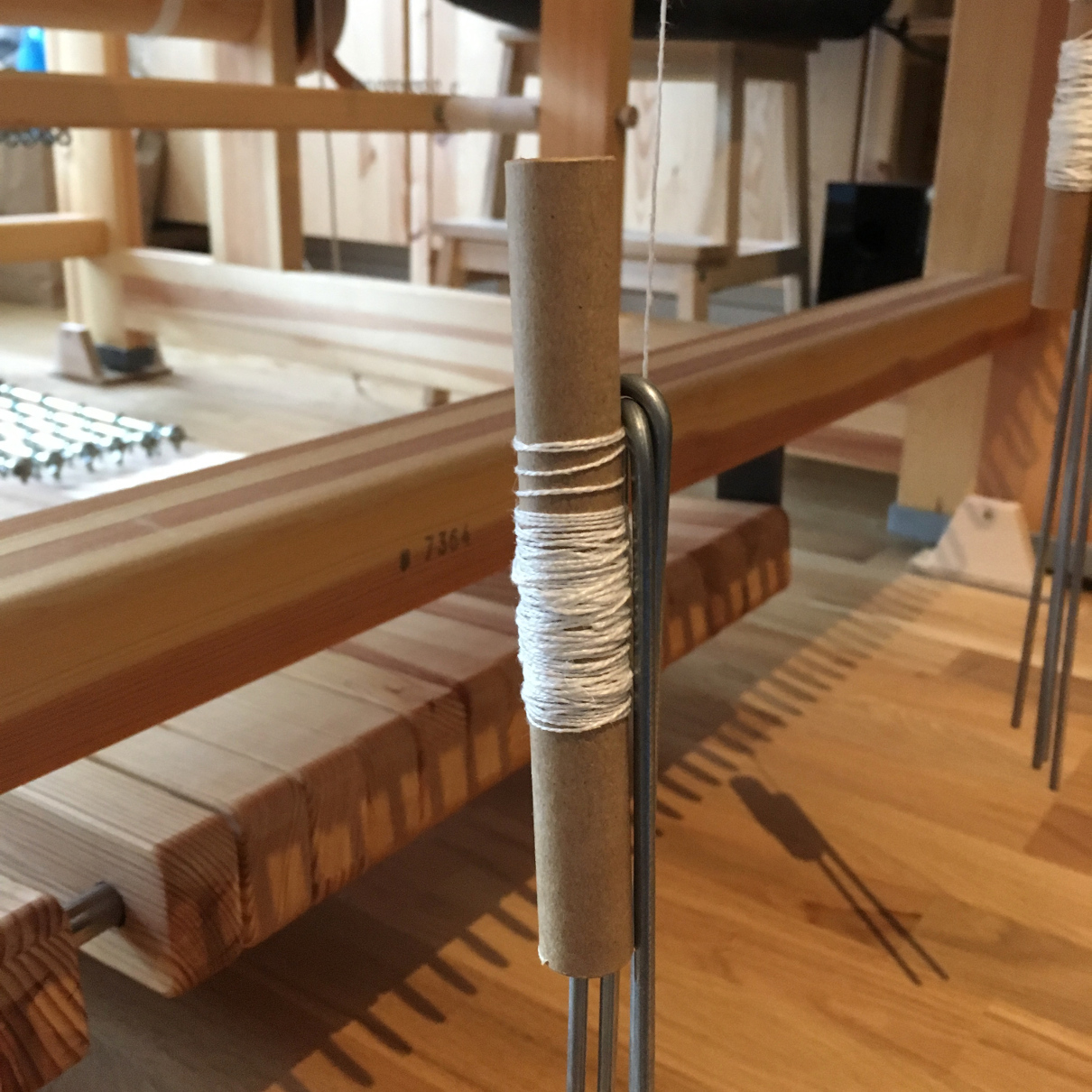

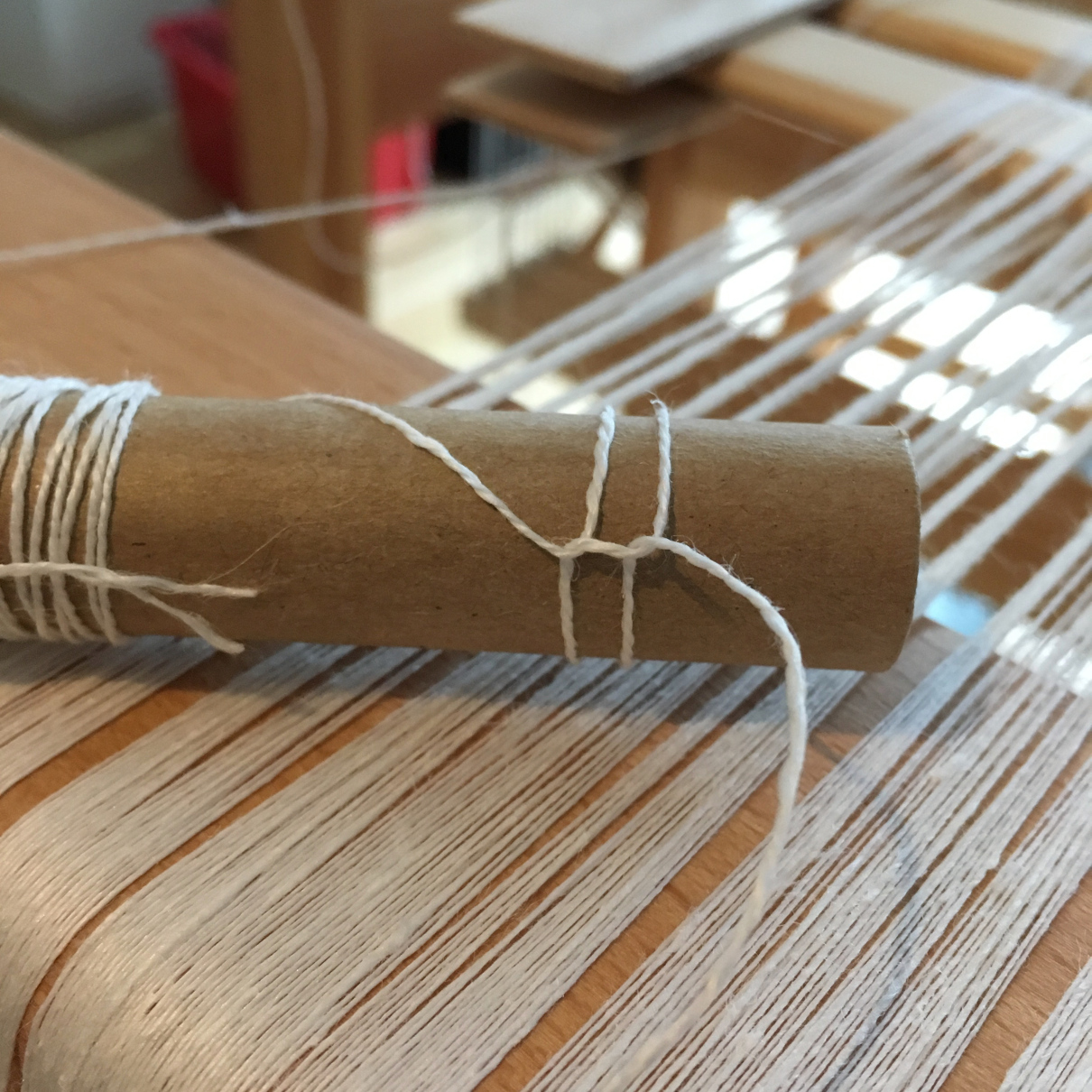

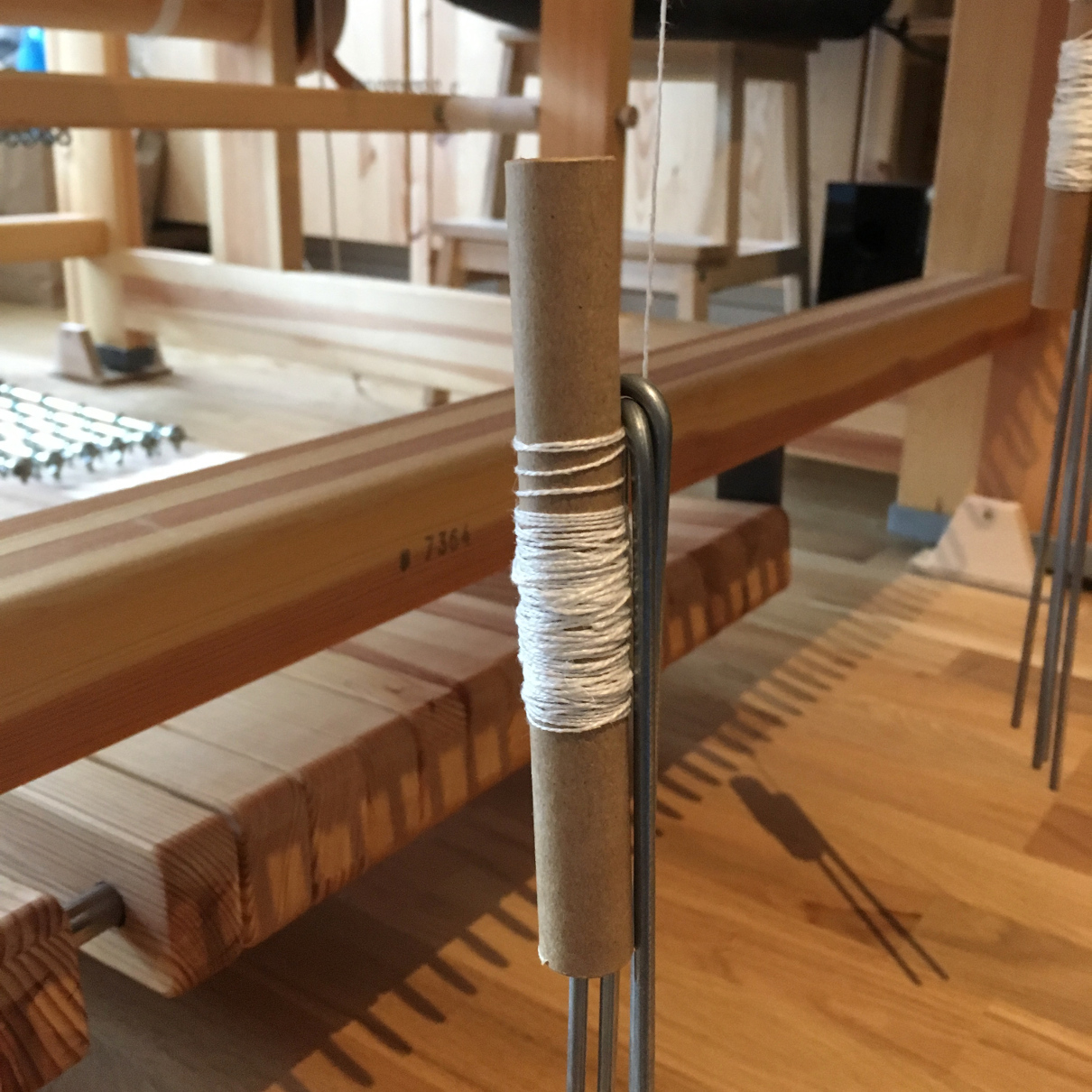

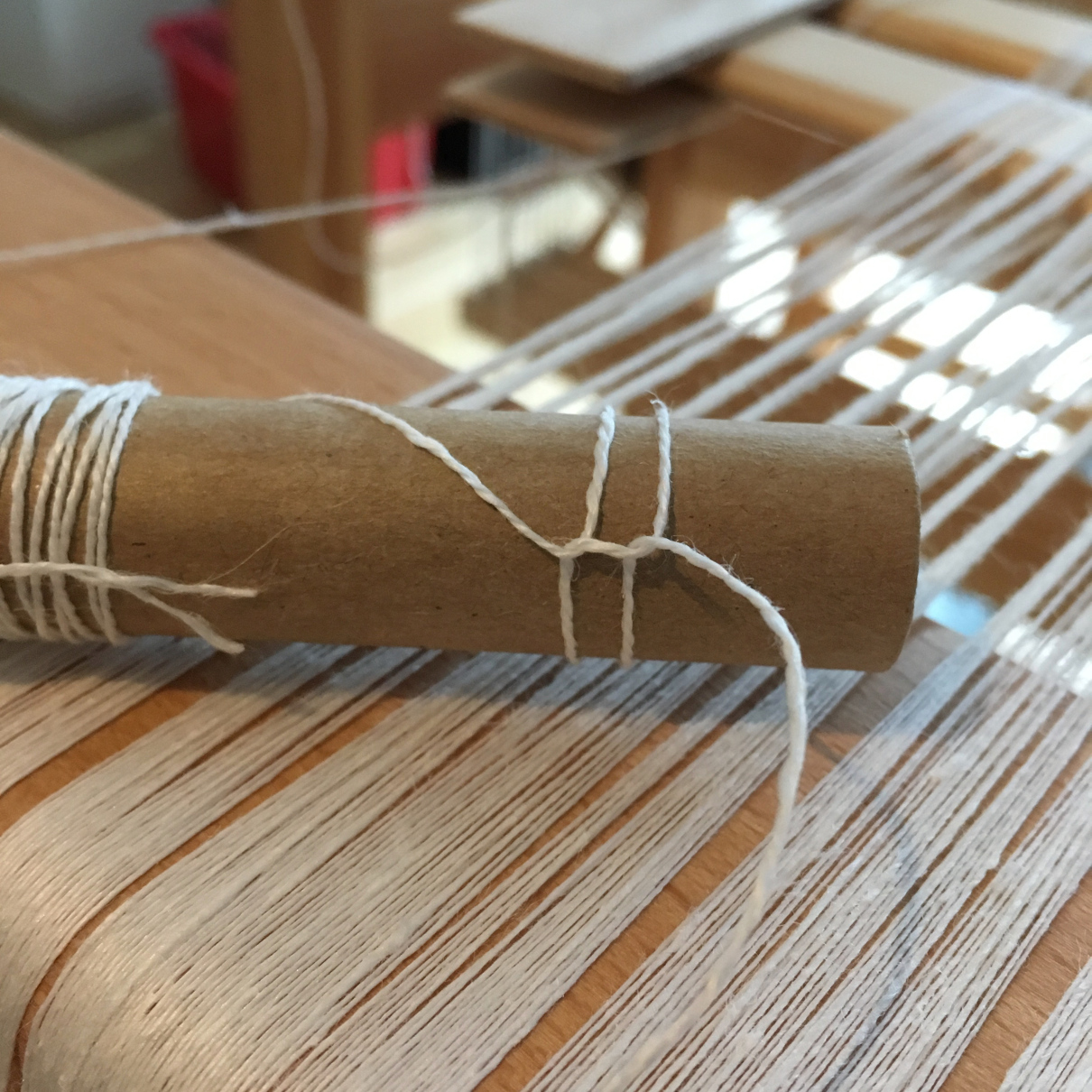

This is why silk weaving looms have extra bobbins for the selvedges:

they are woven in a different structure, typically a plain weave variant with two picks in each shed, and need separate tensioning.

As handweavers who need a single selvedge thread,

we can imitate that somewhat by putting that extra thread on a separate bobbin dangling at the back of the loom.

U-shaped weights intended for drawloom setup are a very good way to weigh down those bobbins,

several can be used if high tension is required.

To prevent the bobbin from unspooling freely,

the thread can be put in a double half-hitch:

this creates enough friction to prevent unwinding,

but is still easy to pull extra length from when the warp is advanced.

Note that due to this thread being on the edge and tensioned separately,

it might need to be sturdier than the main warp yarn.

For instance, my towels and washclothes are woven in 16/1 linen,

but my extra selvedge threads are 16/2 for better solidity.

Making sure to wrap around that unheddled selvedge thread every time is error-prone.

But if we have two shafts to spare, and compatible treadling, we can make it easier.

One thread on each side is put on its own shaft, which is then tied up in plain weave.

This mean the number of structural treadles needs to be even,

with continous treadling that doesn't jump between e.g. treadles 1 and 3.

A 2-2 balanced twill or an 8-shaft satin are great candidates, for instance.

Note that it's in my opinion easier to shuttle if the extra thread is down on the side of the shuttle's entrance.

The tie-ups below are provided in Swedish contramarch style.

Note that this could also be done with a single shaft tied up in plain weave,

and both extra threads on that shaft.

But I find weaving easier if the extra threads aren't in the same shed.

I need to run some tests to see how it affects the finish of the cloth!

The obvious limitation, as explained above, is that odd treadle counts are not compatible.

For example, the very common 5-shaft satin can't benefit from this.

On a countermarch loom, some double-treadling shenanigans might be an option,

but that's a problem for another time!

This also won't magically make tension issues go away:

the shuttle still needs to be passed carefully so it doesn't pull too tight,

and so it gives enough extra weft for take-up.

Iterating on the density of the selvedges in the reed is also vital.

My current WIP has only gotten breakadges on thread 4 on either side, for example:

this means the warp is not dense enough in the last two dents,

causing extra friction.

The result of these drafts are tidy, sturdy selvedges that are easy to weave.

There are no extra warp floats or uneven tension issues,

which makes for faster weaving and better fabric.

Items that use this technique are the pink diamond twill wool scarves and the white linen washclothes.

The white linen towels used unheddled threads

because they're woven in 10-shaft dräll with a 5-shaft satin as the base.